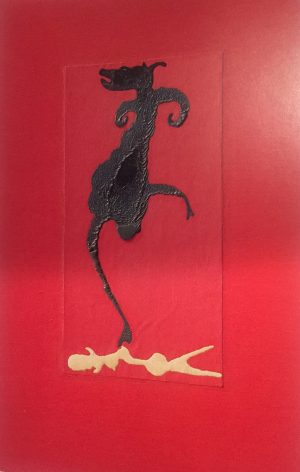

Dezső KORNISS

Friends

- Year(s)

- 1949

- Technique

- oil on paper

- Size

- 21x24,5 cm

Artist's introduction

Dezső Korniss was one of the most important representatives of modern Hungarian painting in the mid-20th century, and co-creator of the legendary “Szentendre Programme”. Throughout most of his career, he has been a banned-and-tolerated artist, who created a body of work that draws on the roots of surrealism and constructivism, with an individual voice and an experimental spirit. According to his monographer Lóránd Hegyi, his synthesizing art represented “the universality of the Latin-Mediterranean-French painterly language, but also its local roots”. Korniss was born in Beszterce, Transylvania in 1908, but grew up in Budapest. As a young man, he attended the open academy of Artur Podolini-Volkmann and then moved to the Netherlands, where he was introduced to the constructivist aesthetic world of the De Stijl group as a high school student. Because of his avant-garde conception, he was not allowed to finish the Academy of Fine Arts in Pest, together with the “progressive young people”. In his early years, he sought contact with art circles of modern spirit in Hungary and in Western Europe. In the 1930s he collected archaic architectural motifs in Szentendre and Szigetmonostor, in Bartók’s footsteps. Together with his friend, Lajos Vajda, he formulated the “Szentendre programme”, which later became famous for combining folk tradition and modernity. He called his style with its vivid, homogeneous splashes of colour, which rewrites traditional motifs into schematised geometric forms, “constructive surrealism”. Although much of his early work was destroyed during the siege, he continued his experiments with renewed vigour after 1945. He joined the short-lived European School, which represented Western modernism in Hungary. He painted surrealist compositions abstracted from archaic masks, bugs and folk ornamentation, he created experimental monotypes, he participated in exhibitions and held a teaching post. After a few optimistic years, the political turn of 1948 made life impossible for Korniss and his intellectual circle. Stigmatised as a “formalist” in the 1950s, the marginalised artist was not allowed to exhibit, but he did not stop creating. His non-figurative works from around 1960, made without a brush, by dribbling lacquer paint, are the best Hungarian analogies of American Abstract Expressionism. In these “written calligraphies”, as Hegyi wrote, the “visual organisation into a system transforms the elementary stains and dribbled lines into rows, into the rhythm of small units”. Young people of the sixties, the progressive creators of the Iparterv generation, discovered Korniss as their role model and master. His geometric design, built of homogeneous patches of colour, was seen as the forerunner of contemporary minimalism and hard-edge. Although Korniss found it difficult to step out of the category of being a banned artist, towards the end of his life he became a cultic figure, a modern master. In his later art he returned to the folk motifs of the Szentendre programme, and then experimented with reduced geometric compositions inspired by minimalism (or suprematism). In 1984 he passed away as a great master of Szentendre art. Gábor Reider

More artworks in the artist's collection »