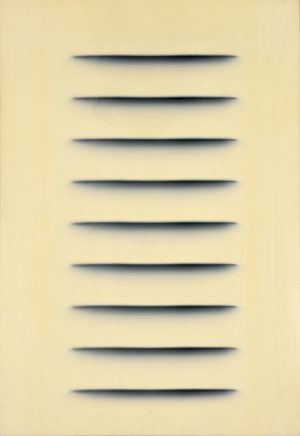

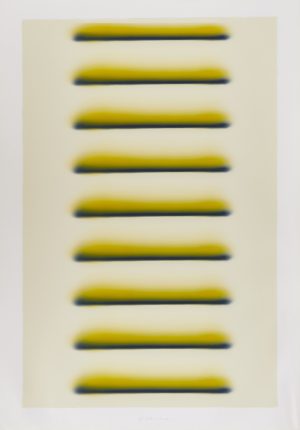

Tamás HENCZE

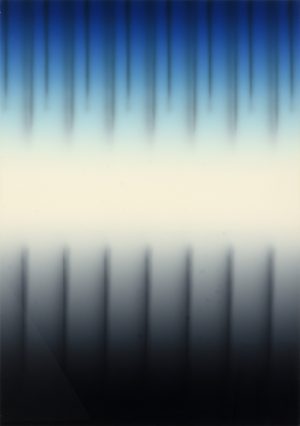

Atmospheric Space

- Year(s)

- 1976

- Technique

- oil on paper

- Size

- 100x70 cm

Artist's introduction

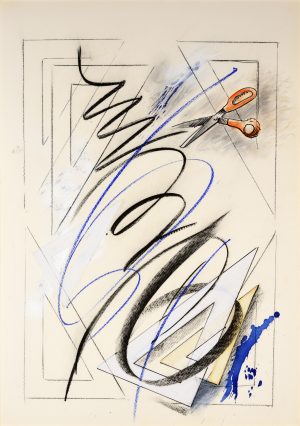

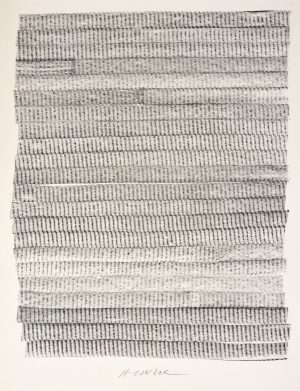

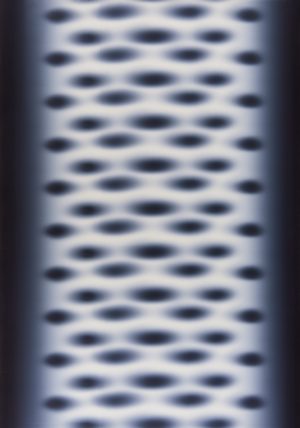

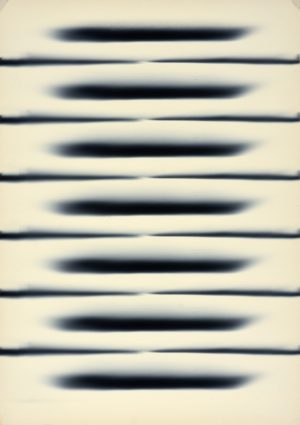

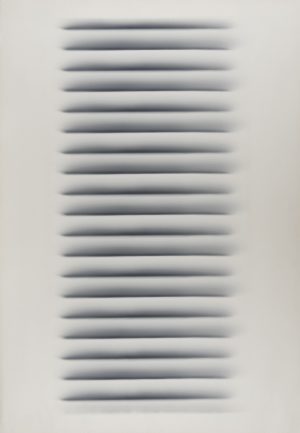

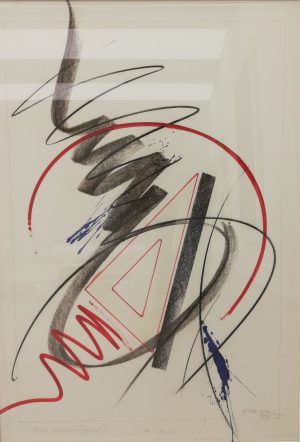

Tamás Hencze considered Dezső Korniss to be his master and the Zugló Circle – which examined abstract art and the theoretical work of Béla Hamvas – as his school. He was a winner of the Kossuth Prize and a member of the Széchenyi Academy of Letters and Arts. His painting practice, which initially focused on the directness of the gesture and the Pop art collage, became individually motivated in the second half of the 1960s. He used stencils and a rubber roller when spreading the evenly applied (black) paint, creating precise transitions and eliciting pulsating spatial effects on the picture plane. The dynamic, repetitive, saturated, fading and empty surfaces appeared as the universal rhythm of life. The structures of his paintings – which "emerged from the point" – coincided with the era's scientific worldview and the minimalist attitude in the arts. His works could also be connected to the Op-art movement, which sought to examine vision. However, Hencze relied on a more complex understanding of perception, introducing the picturesque experience of appearance and disappearance. These works were featured in the unofficial exhibitions at the end of the decade (e.g. Iparterv, 1968) and subsequently in European exhibitions displaying contemporary Hungarian art. In the 1980s, he reinterpreted his images from the beginning of his career: he "froze" huge gestures on large canvases, which were seen as part of the era's postmodern turn. These works were not straightforward gestural paintings but exact reproductions of gestures constructed with templates, rubber cylinders, a few intensely saturated colours, and light, which lent the moment's spatial-material (iconic) reality frozen onto the picture plane. In his work on paper, Hencze occasionally lined up the technical tools connected to the creative process of these more recent gestural images, such as the scissor, the ruler and the various geometric shapes. Katalin Keserü

More artworks in the artist's collection »