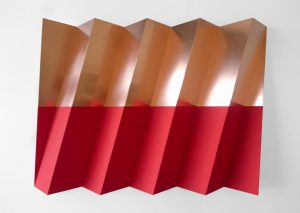

Andreas FOGARASI

Hardwood Floor

- Year(s)

- 2022

- Technique

- wood floor (1915c.), parquet sample board (2021c.), steel strap

- Size

- 100x70x6,5 cm

Artist's introduction

In 2007, the Hungarian pavilion won the prestigious Golden Lion Award at the Venice Biennale. The National Pavilion, which was declared the best, presented a single video installation curated by Katalin Tímár, a work by a then young artist, Andreas Fogarasi, about the remaining physical and intellectual legacy of the Budapest cultural centres from socialism. The slow, documentary, socialist-minimalist aesthetic of this work has attracted attention despite the fact that it is not by its nature suited to be shown on a biennale, as the main point in these large international exhibitions is a quick impact. Fogarasi has a background in architecture, he studied architecture at the Academy of Applied Arts in Vienna, and later his interests steered him to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Alongside his studies in fine arts, he has maintained his interest in architecture, which remains the basis of his art. Since the success of the Biennale, he has had several prestigious international appearances in Mexico City (Proyectos Monclova 2016), Los Angeles (MAK Center 2014, with Oscar Tuazon), São Paulo (Galeria Vermelho 2014), and has exhibited in Leipzig, Madrid, Paris and New York at prestigious institutions such as the Palais de Tokyo, Frankfurter Kunstverein, MUMOK Vienna and Ludwig Museums. His most recent major presentment in Hungary was Skin City - The Skin of the City, a solo exhibition at the Budapest Gallery in 2022. Fogarasi's work is cumulatively complex. It incorporates the ideals of conceptual art, the aesthetics of minimalism, and the exploratory intentions of research-based art. Moving within the conservative framework of drawing, graphic arts and painting, he uses the clean design forms of architecture mixed with a deeply personal, human and familiar sense of the historical past. It presents the built environment, often socialist sites, not only as archaeological artefacts, but also sheds light on complex issues of identity, memory and legacy. In his works, he creates an elegant dialogue between the traditional materials of fine art, such as canvas, graphite and paint, and the remains of buildings from demolition sites. Thus, the universal aesthetics of abstraction, its timelessness and impersonality, are juxtaposed with the substance and historicity of the materials used in the buildings, providing the work with a wide range of associations. Délia Vékony

More artworks in the artist's collection »